"The aim of the Articles may be said to be: In things essential clarity, in things non-essential liberty. This principle is in keeping with the purpose for which the Articles were drawn up and which is stated clearly on the title page, namely that they are 'Articles agreed upon . . . for the avoiding of diversities of opinions, and for the establishing of consent touching true religion'. The Articles were intended to control the teaching within the Church of England and to mark the limits of its comprehension. . . ."

"It is a desperate expedient, as Newman himself later acknowledged, to attempt to read into the Articles by way of distinctions, doctrines which the Reformers rejected."

Thirty-Nine Articles: The Historic Basis of Anglican Faith

A book by David Broughton Knox (Sydney: Anglican Church League, 1967). Revised 1976.

The author: Canon David Broughton Knox, B.A., A. L. C. D., B.D., M.Th., D. Phil. (Oxford), was Principal of Moore Theological College, Sydney, Australia. Ordained in 1941 he served in an English parish and as a chaplain in the Royal Navy before becoming a tutor at Moore College 1947-53. On leave in England he was tutor and lecturer in New Testament at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford 1951-53 and Assistant Curate in the parish of St. Aldale's, Oxford. He became Vice Principal of Moore College in 1954 and Principal in 1959. He was elected Canon of St. Andrew's Cathedral in 1960. His other books include "The Doctrine of Faith in the Reign of Henry VIII" (London: James Clarke, 1961).

David Broughton Knox also founded George Whitefield College in South Africa in 1989.

Chapter Six

The Purpose and Character of the Articles

The Thirty-Nine Articles were not designed as a comprehensive survey of Christian belief or a complete theological system, however summary. Though to some extent they fulfill this role, they are really heads of doctrine drawn up for the purpose of defining the Church of England's dogmatic position in relation to the controversies of the time. This explains their somewhat eclectic character and emphasis. In doctrines which the authors regarded as of central importance their language is very clear, full and forthright, as in the two crucial doctrines of the Reformation, the supremacy of Holy Scripture and justification by faith only. But in some of the other doctrinal areas where Christians differ the Articles are intentionally minimal. For example, in an earlier draft certain literalistic views of the millennium were condemned but in the final form of the Articles this explicit condemnation was omitted.

The aim of the Articles may be said to be: In things essential clarity, in things non-essential liberty. This principle is in keeping with the purpose for which the Articles were drawn up and which is stated clearly on the title page, namely that they are 'Articles agreed upon . . . for the avoiding of diversities of opinions, and for the establishing of consent touching true religion'. The Articles were intended to control the teaching within the Church of England and to mark the limits of its comprehension. Comprehension is a relative term. Every association must be comprehensive and yet there must be an agreed limit to that comprehension, either explicit or implicit, if the association is to remain in being.

Attempts are made from time to time to reconcile the Articles with doctrines valued because of their place in Catholic tradition. The best known attempt in this direction is that of John Henry Newman in Tract 90. The attempt still continues. Thus, the Reverend K. N. Ross, Vicar of All Saints', Margaret Street, London, wrote: 'It is not difficult on most issues to show that there is no incompatibility between the teaching of the Church of England and the tridentine decrees.'i

It is claimed that the Articles are designedly ambiguous and that the Reformers deliberately used ambiguous distinctions in order to avoid condemning 'Catholic' doctrine while maintaining a reformed position. This would be an extraordinary action if it were true, as it would defeat the object for which the Articles were drawn up, which was the 'avoiding of diversities of opinions, and for the establishing of consent touching true religion'. Deliberate ambiguity is a device not for the avoiding of diversities of opinions but for allowing them. Nor is permission to differ equivalent to the establishing of consent touching true religion.

On those matters which the Articles touched the Reformers intended them to be unequivocal, and there is no evidence that they failed in any important point in this. An example of the inadequacy of the method which seeks to allow room for unreformed doctrines to be held along with assent to the Thirty-Nine Articles is the way the notion of sacrifice is treated in the Articles and in some modern commentaries on them. Article 31 'Of the one Oblation of Christ finished upon the Cross', affirms that Christ's offering of Himself was made once, and 'is that perfect (that is, completed, perfected) redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction, for all the sins of the whole world'. The Article draws the deduction that 'the sacrifices of Masses, in the which it was commonly said, that the Priest did offer Christ' as a propitiatory sacrifice for sins were altogether erroneous. John Henry Newman seized on the use of the plural 'sacrifices of Masses' to make a distinction. He wrote: 'Here the sacrifice of the mass is not spoken of, in which the special question of doctrine would be introduced; but "the sacrifice of masses", certain observances for the most part silent and solitary, which the writers of the articles knew to have been in force in time past . . .'ii

The same distinction is repeated by K. N. Ross: 'It can scarcely be an accident that there is no attack on the sacrifice of the Mass, but only on "sacrifices of Masses".'iii Similarly E. J. Bicknell wrote: 'It is not "the sacrifice of Mass" but the "sacrifices of masses" that is condemned: not any formal theological statement of doctrine -- for such did not exist -- but popular errors (quod vulgo dicebatur).'iv

The purpose of making these distinction between the singular and the plural is to preserve the possibility of believing that the Lord's Supper is primarily a sacrifice offered to God. But the distinctions made do not make any difference to the teaching of the Article which excludes the notion of sacrifice as strongly as words are able to do. The title of the Article speaks of 'the one Oblation of Christ finished upon the Cross', and the Article itself is concerned not merely with the sufficiency of Christ's sacrifice but with its completeness in the past. It was once made to provide perfect redemption, perfecta redemptio. [Charlie's note: Cf. Hebrews 7:23-28].

The notion that sacrifice is the way for sinners to worship the Almighty is congenial to human thought. All religions contain it and it is central to Christianity. But Christianity recognizes that man is unable to offer any sacrifice worthy to obtain God's favour. Christ alone can make and has made the one sacrifice for the sins of the whole world. This propitiatory work of Christ is finished. The clear, resounding ephapax, 'once for all', rings like a bell through the pages of the Epistle to the Hebrews, effectively excluding any concept of Christ's continuing offering of His sacrifice in heaven or of our continuing it on earth. It is true that the New Testament writers use the Old Testament vocabulary of sacrifice to describe Christian worship under the New Covenant. For they had no other vocabulary available to express the Christian's worship (i.e., the honour of God) than sacrificial terms which were the worship terms of the Old Testament. But all the New Testament uses of this Old Testament language are plainly metaphorical; for example, Hebrews 13:15, 16 'Let us offer up a sacrifice of praise to God continually' where the following words 'that is, the fruit of lips which make confession to his name' clearly indicate a metaphorical use of the concept of sacrifice. And in the next verse Christian generosity to others is the way which the Christian worships and honours God. 'With such sacrifices God is well pleased.' Christian generosity is called 'a sacrifice', not in the modern sense of a going without, but in the Old Testament sense of worship. However, the idea of a literal and not merely metaphorical offering as the way to worship God is so endemic to human thought that it reasserts itself whenever the Christian community weakens in its apprehension that the one perfect sacrifice for sinners has already been made, and that we are accepted by God (or justified) through faith, on the ground of the merits of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ and His offering once made on Calvary.

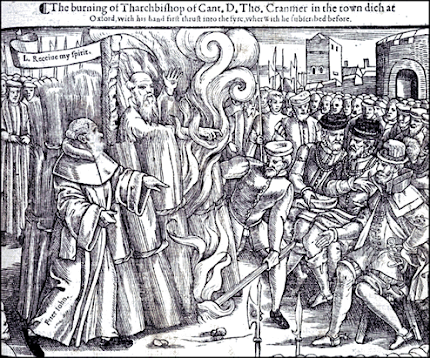

The idea that we have a literal sacrifice to offer by way of worship re-established itself during the centuries, and the Lord's Supper was the natural ordinance on which this concept was grafted. As a consequence those who look to tradition as the source of theology give a prominent place to the sacrificial interpretation of the Lord's Supper. The Reformers were determined to exclude this idea as an aberration from New Testament teaching, and most onlookers would think that they had achieved this fairly successfully in the Prayer Book, Articles and Ordinal. For example, Leo XIII's bull, Apostolicae Curae, proceeds on the assumption that it is self-evident that the Reformers have excluded the notion of any real sacrifice in the Lord's Supper.

It is a desperate expedient, as Newman himself later acknowledged, to attempt to read into the Articles by way of distinctions, doctrines which the Reformers rejected. Deliberate ambiguity was against their purposes. Accidental ambiguity in matters of such cruciality and controversy is unlikely to be found in a document brought to finality over a period of years, and an examination of the text confirms its absence.

The other formularies of the Church of England, for example, the Book of Common Prayer, ought to be interpreted in the light of the Articles and not the Articles in the light of the Prayer Book, because this latter course would be reversing the purposes for which the Articles were agreed upon. The Articles were designed to be the agreed upon doctrinal basis within which the Prayer Book is to be used and interpreted.

Next Chapter

Next Chapter

[For other chapters of this book see: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4.1, Chapter 4.2, Chapter 5.1, Chapter 5.2, Chapter 5.3, Chapter 5.4, Chapter 5.5.]

iThe Thirty-Nine Articles, (London, 1957), p. 78.

iiTract 90, p. 59.

iiiIbid., p. 78.

ivA Theological Introduction to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England (London, 1955), p. 525.

The Eighth Sunday after Trinity.

The Collect.

O GOD, whose never-failing providence ordereth all things both in heaven and earth; We humbly beseech thee to put away from us all hurtful things, and to give us those things which be profitable for us; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Collect.

O GOD, whose never-failing providence ordereth all things both in heaven and earth; We humbly beseech thee to put away from us all hurtful things, and to give us those things which be profitable for us; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment