- "Apparently, one of the issues that sparked off the Oxford Movement and the Anglo-Catholic Tractarian movement was that morning prayer was the only service being celebrated on Sunday mornings and that service does not provide for a sermon. Not only was there no communion being administered but there was no preaching and no instruction being given. Apparently, one of the issues that sparked off the Oxford Movement and the Anglo-Catholic Tractarian movement was that morning prayer was the only service being celebrated on Sunday mornings and that service does not provide for a sermon. Not only was there no communion being administered but there was no preaching and no instruction being given. On this point we are indebted to the Anglo-Catholics for restoring an emphasis that the English Reformers would have wanted to continue, including a celebration of the liturgy and eucharist on a weekly basis."

Since someone has accused me of being inaccurate let me emphasize the last portion of that paragraph once more:

- On this point we are indebted to the Anglo-Catholics for restoring an emphasis that the English Reformers would have wanted to continue, including a celebration of the liturgy and eucharist on a weekly basis.

Because of my comments being taken out of context it becomes necessary to comment further. There was a lack of attendance at church services for various reasons. According to the practice of the time if no more than three persons were in attendance, then holy communion could not be administered. Hence, holy communion was not administered more than a couple of times per month. Also, only morning prayer was being offered because of this and that without a sermon. In support of my thesis I quote from the following article on a pro-Anglo-Catholic website:

- In the early Church, it was the normal practice for every baptised Christian to receive the Sacrament of Holy Communion at least once a week. But gradually the practice changed. It was still understood that a Christian would attend a celebration of the Liturgy every Sunday, but attending the Liturgy did not necessarily mean receiving the Sacrament. By the early 1500's, most Christians in Western Europe other than clergy or monastics received the Sacrament once a year, at Easter. The rest of the year, a typical devout Christian would attend the Liturgy every Sunday, but, not understanding Latin, would spend most of his time praying silently or in an undertone in his pew, while the priest read the Liturgy in Latin in an undertone at the altar some distance away. Partway through the service, a bell would ring and the priest would hold up the consecrated bread and wine, and the private prayers would stop for a moment as all eyes focused on what Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself had appointed as the vehicle of His abiding presence among His people. Then the private prayers would resume.

- It was the hope of the sixteenth-century Reformers to restore the ancient practice of the Church by celebrating the Liturgy in the language of the people, and encouraging the people to participate, not only by listening to the readings and joining in the prayers, but also by reverently receiving the Sacrament at every Liturgy they attended. In England, at least, they only partly achieved their goals.

- The English Reformers provided that, at every celebration of the Liturgy, after the prayers and Bible readings and the sermon and Creed, there would be a general confession of sins, and that those intending to receive the Sacrament would come forward and kneel at the altar rail to repeat the Prayer of Confession, while the rest of the congregation would remain in their pews, and recite the prayer along with them. The priest would turn around and see how many worshippers were at the rail. If there were at least three, he would place the bread and wine on the altar and proceed to consecrate them. Unless there were at least three, he was to close the service at that point with a Blessing and Dismissal. The theory was that when the people were thus dramatically reminded that receiving the Sacrament was the reason for having the service, they would flock to receive. Instead, they simply got used to the idea that the Liturgy would be celebrated only a few times a year.

- On most Sundays, the Sunday morning service in most parishes consisted of Morning Prayer (one Reading from the Psalms, one Old Testament Reading, one New Testament Reading, interspersed with Prayers and Hymns, taking about fifteen minutes), Litany (prayer with responses, taking about eight minutes), and Ante-Communion (first part of the Liturgy, with the Ten Commandments, a reading from an Epistle and another from a Gospel, the Creed, plus a few hymns and prayers, lasting about fifteen minutes). As the years passed, this was reduced in many parishes to Morning Prayer with Hymns and Sermon.

- Then, in the 1830's, several lecturers at Oxford University, reading their copies of the Book of Common Prayer, noticed that this was not the intended state of affairs. The Prayer Book provided for a sermon at the Liturgy, but not at Morning Prayer, for the taking of a collection at the Liturgy, but not at Morning Prayer. In every way it was clear that the compilers of the Prayer Book had intended the Liturgy to be the principal service on every Sunday and Feast Day. So the lecturers got busy and wrote a series of pamphlets explaining this and various related points to their readers. They called the pamphlets Tracts For the Times, By Residents in Oxford, and the public referred to them as The Oxford Tracts.

- From: The Oxford Tractarians: Renewers of the Church [http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bio/249.html]

I will correct myself here. The Prayer Book called for no sermon at Morning Prayer but a sermon was offered anyway. The Tractarians rightly saw that the Reformers intended for the principal service to be Holy Communion, in which the Prayer Book rubrics did call for a sermon.

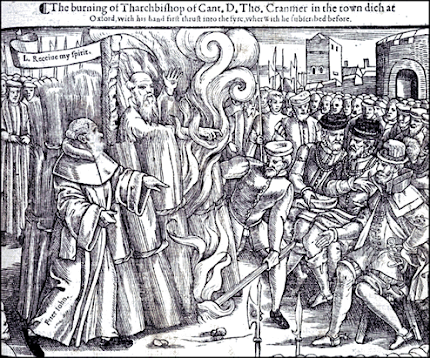

Also, my original point remains the same: Holy Communion had fell into disuse because of lack of attendance at holy communion, which evolved into a tradition of only observing Morning Prayer, the rubrics of which in the Prayer Book provided for no sermon (though a sermon was being offered anyway). I would concur that the English Reformers never intended such a state of affairs. Anglo-Catholics were right to call for a reform of the services and a return to what the original English Reformers had intended, that being a weekly celebration of the Lord's Table as the principal service. That does not, however, entail adapting Anglo-Catholicism, hook, line and sinker. Anglo-Catholicism remains heretical on the central issues of the Gospel, including justification by faith alone and sola scriptura, as well as the Romish additions of the other sacraments and prayers to Mary in their so-called American Missals.

Hope this helps,

Charlie

No comments:

Post a Comment